A New Mathematical Operating System for AI

From Flat Gradients to Jet Geometry: Differentiating the Space Instead of the Network

TL;DR

Most current AI runs on a flat, first-order OS: everything is a tensor in R^n, and training is driven primarily by first-order gradients. If you want anything richer—HVPs, curvature signals, better memory, you have to stack grad, jacfwd, jacrev, jvp, vjp and manage extra graphs, extra passes, and extra bugs. The result in practice: unstable training, brittle generalization, and ugly workarounds for hierarchy (hyperbolic “patches”) and memory (KV caches, ad-hoc recurrence).

This post proposes a new mathematical OS for AI: instead of differentiating the program, we differentiate the space. Internal states are jets on curved manifolds (hyperbolic for hierarchy, toroidal for phase/memory). A single pass on jet-valued states gives you value, gradient, and useful second-order information along the encoded directions as one object, and standard AD primitives (JVP, VJP, HVP) can be understood as consequences of the jet algebra and its functoriality. For AI engineers, this means:

geometry and hierarchy built into the representation space,

structured, low-interference memory from topology,

higher-order training signals available by changing the state type, not by wiring up new AD pipelines.

1. Introduction

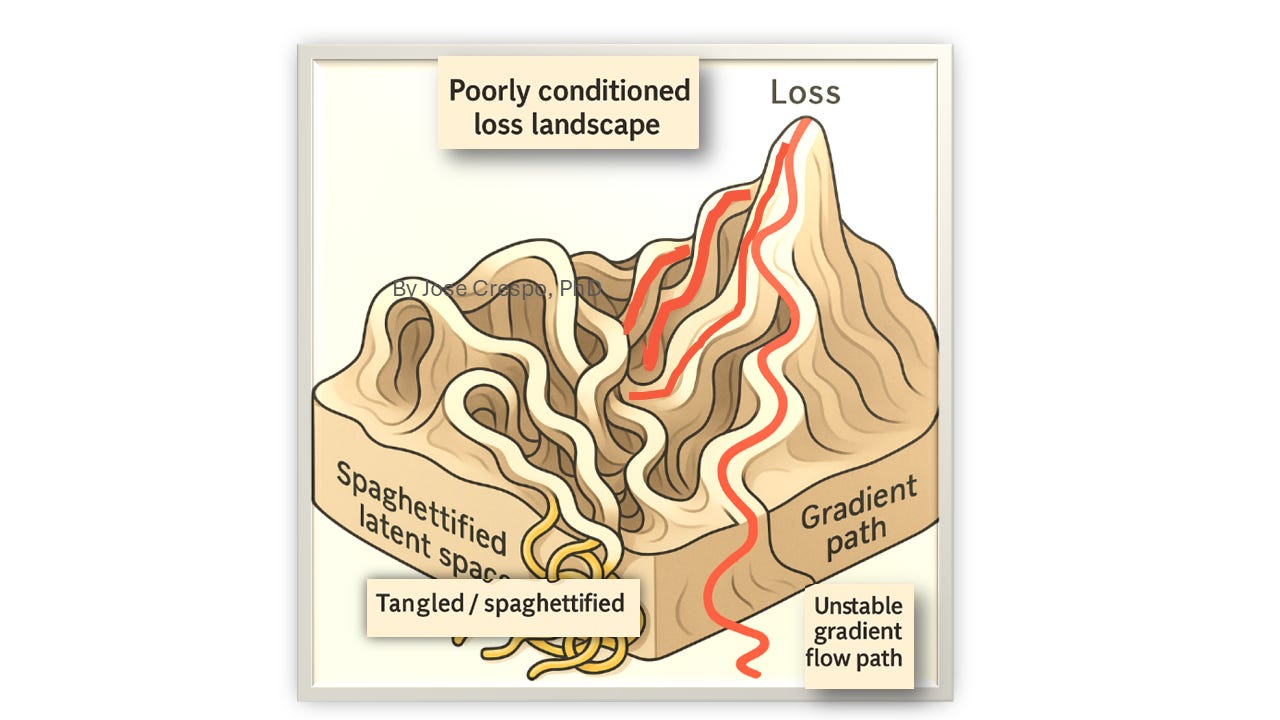

Modern AI runs in what we will call the Euclidean first-order regime. Internal states are flat tensors in R^n, and training is driven almost entirely by first-order gradients in those coordinates. Contemporary automatic differentiation (AD) frameworks compute these gradients exactly on their primitives (up to floating-point error), but they do so as transformations on tensor programs— grad, jacfwd, jacrev, jvp, vjp —each of which can be viewed as defining a new graph in flat space. Large-scale optimization then unfolds on poorly conditioned Euclidean landscapes, and as models grow, we repeatedly see unstable gradients, tangled latent trajectories, memory interference, and brittle compositional behavior.

We treat these not as incidental engineering glitches, but as signs that the underlying mathematical substrate is misaligned with the phenomena we want to model.

This article proposes a different substrate: a geometric, jet-based operating system for AI. Instead of keeping states as points in R^n and repeatedly differentiating the program, we differentiate the space itself.

Internal states are jets on curved manifolds: truncated Taylor expansions living in Jk(M), with M (i.e. Toroid or Hyperbolic) chosen to match the semantics of the task—for example, hyperbolic manifolds for hierarchical representations and tori for periodic, phase-like memory. Dual numbers and higher-order jet algebras provide an intrinsic semantics for differentiation: a single semantic pass through the network propagates jet-valued states via the functorial jet-lift Jk(F), so value, gradient, and selected low-order higher-derivative information along the encoded directions appear as components of one geometric object rather than as separate AD constructions.

From this viewpoint, hallucinations, gradient pathologies, “spaghettized” latents, and memory collisions are reinterpreted as consequences of forcing hierarchical, periodic, and higher-order structure into flat Euclidean embeddings while using almost exclusively first-order dynamics. By formulating differentiation and parameter updates at the level of jet functors, and by analyzing how curvature and topology shape the resulting flows, we argue that many weaknesses of current architectures arise from this flat, first-order foundation itself—and that a geometric, jet-based operating system for AI is a more appropriate starting point than further tuning of the existing one.

2. The Euclidean First-Order Regime

We begin by making precise what we mean by the Euclidean first-order regime that characterizes essentially all contemporary large-scale AI systems.

2.1. Representations as Euclidean tensors

Let X denote an input space (e.g. token sequences, images, or states), and let a model be a parametrized map:

In the next subsection we will see that the same Euclidean assumption is inherited by the learning dynamics: automatic differentiation computes exact gradients of these tensor maps in flat coordinates, and optimization operates on this Euclidean parameter and representation space using almost exclusively first-order information.

2.2. First-order gradient dynamics

Training consists in minimizing an empirical loss

and practical algorithms such as SGD, Adam, or their variants implement discrete approximations of this ODE.

In exact arithmetic, this gradient is mathematically exact: no finite-difference limits are taken, and the derivatives of the primitives are analytic. However, the dynamics of θt\theta_tθt under these gradients are governed by the geometry of a high-dimensional loss surface embedded in a flat parameter space RP\mathbb{R}^PRP.

Two structural features follow:

2.3. Geometric and numerical failure modes

Within this Euclidean first-order regime, well-known pathologies can be interpreted as geometric and numerical phenomena:

Memory interference.

In recurrent architectures and transformer key–value caches, different histories are encoded as trajectories in a shared Euclidean latent space. Without any topological notion of “distinct memories,” trajectories corresponding to different sequences can intersect, overlap, or collapse onto nearby regions, leading to interference and collisions in retrieval and generation.Brittle compositional behavior and hallucination.

Since all structure is represented in a flat vector space and learning is driven by local first-order updates, there is no guarantee that compositional relations (e.g. hierarchy, nested scope, periodic structure) are preserved under extrapolation. The model may fit training statistics while mapping novel compositions to geometrically arbitrary regions of latent space, resulting in incoherent or fabricated outputs.

We do not claim that these phenomena can be uniquely or exhaustively explained by geometry alone, nor that curvature and topology are sufficient remedies. However, we take the above as evidence that the combination of (i) Euclidean representation spaces and (ii) purely first-order optimization constitutes a rigid and fragile foundation for intelligence at scale. The remainder of this work develops an alternative substrate—jets on curved manifolds—in which higher-order structure, curvature, and topology are built into the objects being optimized, rather than retrofitted as after-the-fact regularizers or architectural hacks.

2.4 The Hidden Geometry of Neural Networks (the smoking gun )

Up to now we have treated the Euclidean first-order regime as a design choice:

Representations as Euclidean tensors (Section 2.1):

All internal states live in a single global coordinate chart R^n. No intrinsic structure—hierarchy, orientation, periodicity—is carried by the space itself.Training as first-order gradient flow (Section 2.2):

Optimization dynamics unfold in a flat parameter space R^P, driven almost exclusively by first-order derivatives computed in Euclidean coordinates.Failure modes arising from this flatness (Section 2.3):

Memory interference, unstable trajectories, brittle composition, and hallucinations emerge when complex structure is forced into a space with no geometry to support it.

What is less widely appreciated—and central to the foundational critique of this OS—is that even in this flat R^n setting, modern neural networks do not remain geometrically flat.

The geometry cannot be avoided.

Even when everything is implemented in flat R^n, modern neural networks already induce a nontrivial connection, and in practice exhibit nonzero curvature observable directly in their Jacobians.

The Euclidean OS is geometrically broken by its own internal transformations.

Here are the mathematical “tools” for visualizing those hidden curvatures in current AI frameworks:

2.4.1. The Jacobian as a Transport Map

Now we take a single frozen block

From an optimization standpoint, these blocks are used to assemble gradients. From a geometric standpoint, they encode something much stronger:

In conclusion:

So as you see we have the collection V to be connected via the transport operator Gamma

where B again is the index set of sites (tokens, patches, slots, etc.).

This observation has been made explicit by Gardner (2024), but it also follows directly from the semantics of AD:

the representation graph becomes a connection graph, and the Jacobian blocks become its connection coefficients

2.4.2. Loops, holonomy, and curvature inside flat coordinates

Once transport maps exist, loops become meaningful.

Crucially, all of this happens inside the supposedly flat coordinates of R^n. There is no curved manifold in the architecture, no Riemannian layer, no special geometry—just the Jacobian of the block you already run.

The network pretends to occupy flat R^n,

but its own Jacobian-level transport shows that it behaves, operationally, like a non-flat connection on a bundle.

Here is where the model’s curvature is created: Jacobian transport around loops of tokens reveals non-trivial curvature in the network’s internal geometric structure:

For a much deeper mathematical explanation, I strongly recommend you read my other two articles about:

Holonomy I

3.From emergent curvature to designed geometry: Jets and Curved Manifolds as a Computational Substrate

This is the point at which the foundations crack.

If every serious neural model already defines a connection and empirically exhibits curvature through its Jacobians, then the real architectural choice is not:

Euclidean vs geometric methods,

but:

accidental geometry vs designed geometry.

Having identified the structural limitations of the Euclidean first-order regime, we now introduce the central objects of our alternative architecture: jets on curved manifolds. These objects unify representation, memory, and differentiation within a single geometric–algebraic framework.

3.1. From points to jets

This representation encodes no intrinsic derivative or neighborhood structure; all higher-order information must be inferred implicitly through training, typically with only first-order gradients.

We instead represent an internal state not by a point but by a jet:

where M is a smooth manifold (hyperbolic or toroidal in our setting). A jet encodes:

zeroth-order information (the point x),

first-order information (the tangent vector),

higher-order derivatives (curvature, torsion, etc., up to order k).

Jets can be realized algebraically using:

dual numbers for k=1

higher-order dual numbers / truncated polynomial rings for general kkk.

Thus, each internal state carries an intrinsic local Taylor model of itself.

This replaces the “pointwise” representation of modern networks with a much richer local geometric object.

3.2. Hyperbolic manifolds for representation

exponential volume growth with radius,

natural embeddings of trees into geodesics,

concentration of distances that reflect semantic hierarchy.

The manifold geometry thus organizes feature structure, rather than requiring the network to learn hierarchy from scratch inside a flat Euclidean space.

3.3. Toroidal manifolds for memory

Recurrent and stateful components of neural architectures (e.g., attention caches, recurrent channels) must maintain distinct trajectories for different sequences. In Euclidean latent spaces, trajectories can cross, collapse, or interfere, causing memory collisions or blending of contexts.

periodic structure,

phase variables,

winding numbers w∈Zmw \in \mathbb{Z}^mw∈Zm that serve as global, discrete invariants of recurrent dynamics.

A memory trajectory on a torus acquires a winding number vector that cannot be erased by smooth deformations. The pair

thus separates distinct histories even when their instantaneous positions are nearby.

3.4. Differentiation as an intrinsic algebraic operation

In standard deep learning, differentiation is executed by an external automatic differentiation engine operating on Euclidean tensors. In contrast, jets carry their own algebraic differentiation structure:

The first-order jet implements the chain rule via evaluation on dual numbers.

Higher-order jets implement higher-order chain rules via truncated polynomial algebras.

The tangent and cotangent lifts induced by jets correspond to Jacobian–vector products (JVPs) and vector–Jacobian products (VJPs), respectively.

Hessian–vector products (HVPs) arise from functorial compositions JVP∘VJP and VJP∘JVP, depending on mode.

Thus, differentiation is reinterpreted not as a separate numerical pass over a computational graph, but as a native operation in the jet algebra of the manifold.

3.5. A categorical formulation

Jets and their transformations naturally form a category:

This categorical viewpoint unifies representation, memory, and differentiation under a single mathematical framework. Every component of the architecture—layers, updates, recurrences, memory—becomes explicitly geometric and functorial.

Summary of Section 3

Jets on curved manifolds replace the Euclidean first-order substrate with a geometric object that:

encodes higher-order local information via truncated Taylor expansions,

organizes representation via hyperbolic structure,

organizes memory via toroidal topology and winding invariants,

internalizes differentiation via jet algebra,and

supports functorial composition for higher-order derivatives.

This sets the stage for Section 2, where we formalize JVP, VJP, and HVP as categorical transformations and show how learning dynamics on jet-valued states differ from their Euclidean first-order counterparts.

4.Bringing all components together within the framework of a new AI Operating System

The previous sections treated the pieces of the proposal in isolation: jets on curved manifolds as state, hyperbolic spaces for representation, tori for memory, and categorical differentiation as the core calculus. In this final section we reassemble them explicitly as an operating system for AI, and show how familiar OS notions map cleanly onto geometric objects and functors.

4.1. From operating systems to differential geometry

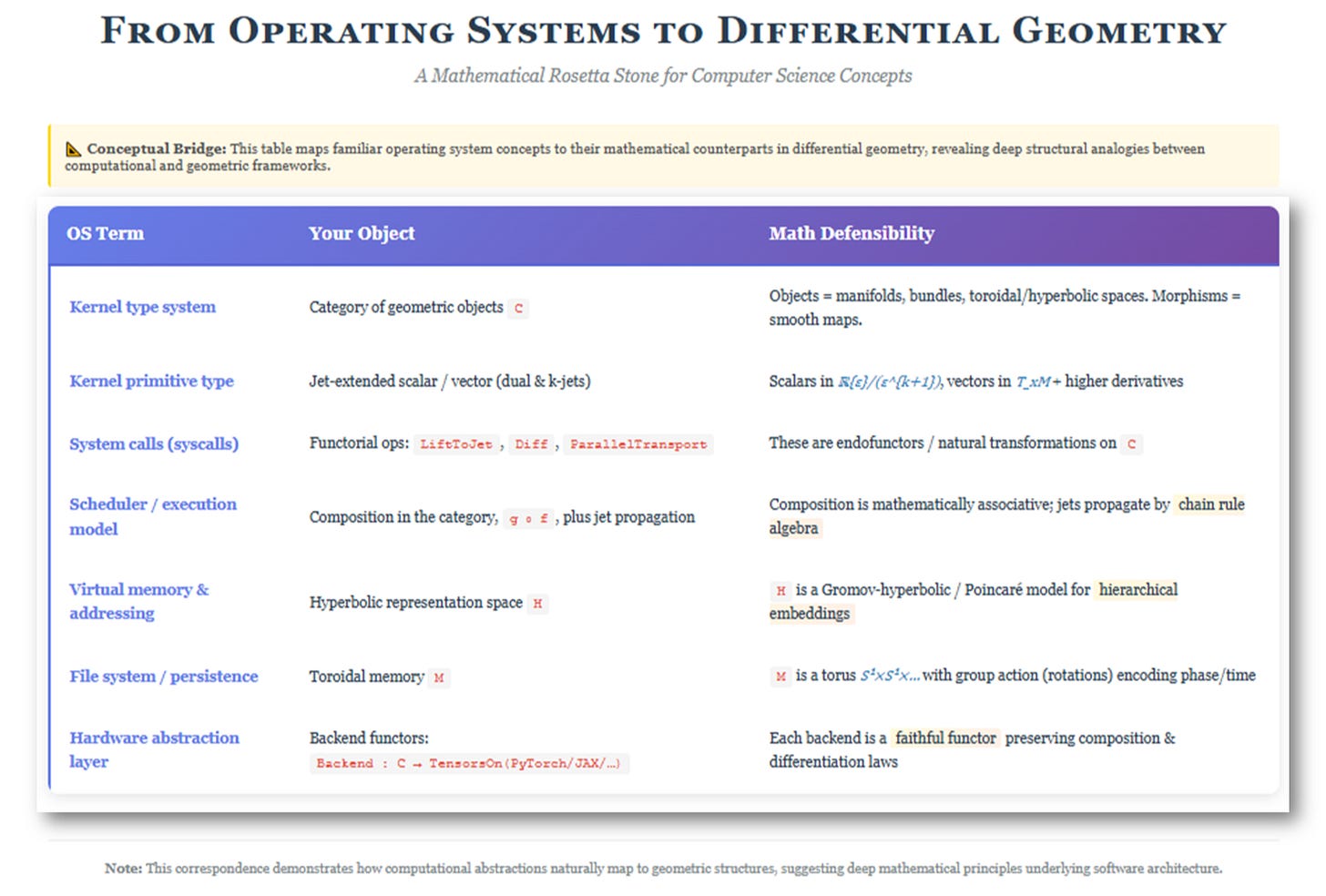

Figure 5 (“From Operating Systems to Differential Geometry”) is a small Rosetta stone. The left column lists standard OS concepts; the middle column shows the corresponding object in our framework; the right column explains why each mapping has a precise mathematical meaning.

The point of the table is not metaphor. Each row replaces an OS-level abstraction by a well-defined geometric or categorical structure.

4.2. Geometric AI Operating System architecture

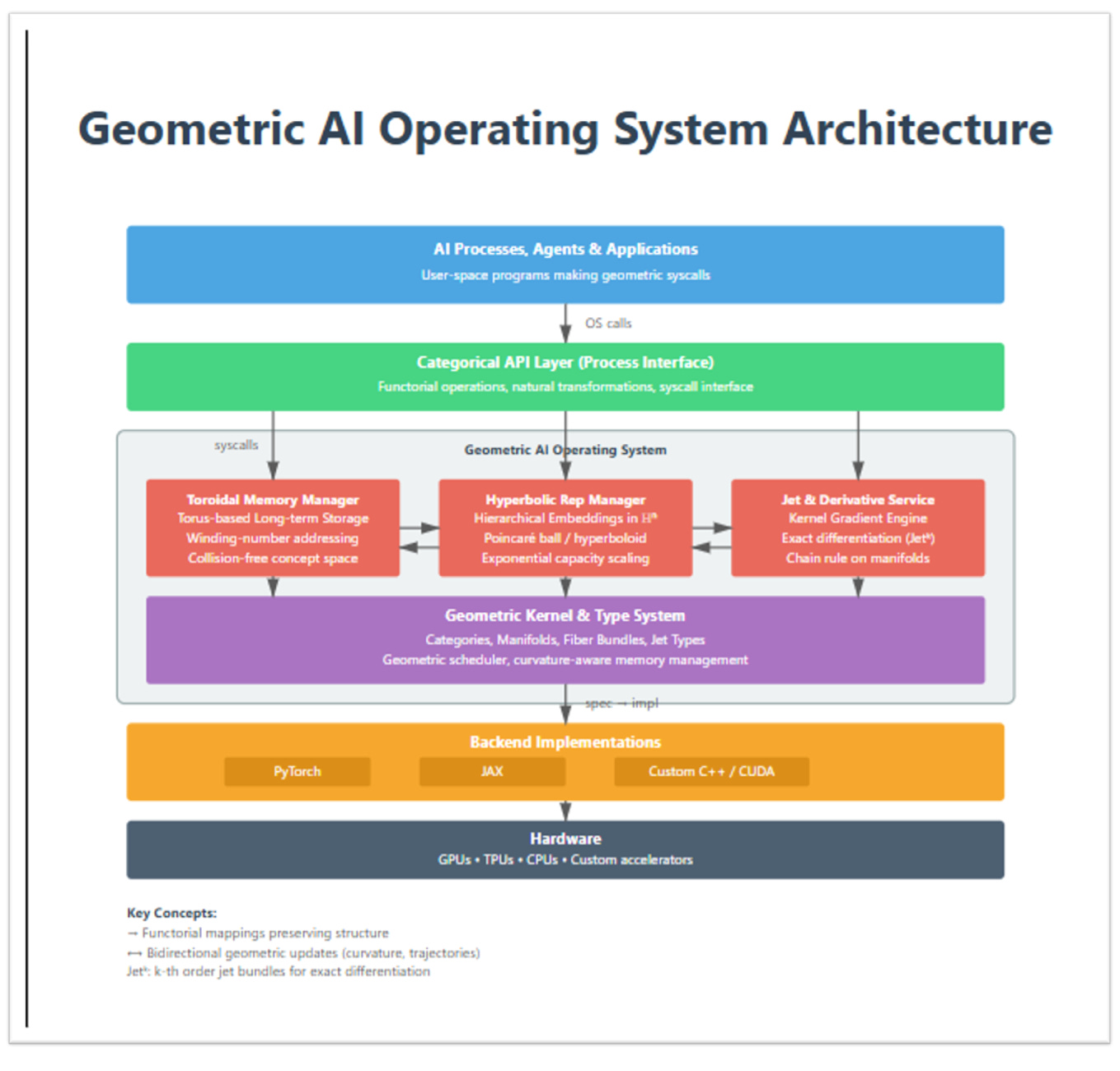

Figure 6 (“Geometric AI Operating System Architecture”) shows how these pieces stack into a full system.

User space: AI processes, agents, applications.

At the top sit “programs” in the usual sense: agents, training loops, planning routines. They no longer speak tensors directly; they make geometric syscalls against an abstract API.Categorical API layer (process interface).

This layer exposes functorial operations and natural transformations (LiftToJet,PushForward,PullBack,ParallelTransport, etc.). From a programmer’s point of view, this is the interface for “differentiate this map”, “transport along that trajectory”, or “read/write from toroidal memory”.Geometric AI Operating System (core services).

Inside the OS box sit three main managers:Toroidal Memory Manager - implements long-term storage on M, with winding-number addressing and interference-aware memory layouts.

Hyperbolic Representation Manager - manages embeddings in H, ensuring that hierarchical structure is aligned with the ambient negative curvature.

Jet & Derivative Service - the “gradient kernel”: it maintains jet-valued states, executes jet lifts J^k(F), and returns algebraically exact first-order and selected higher-order information (up to order k and floating-point error) in a single semantic pass.

All three share a common view of state: everything is a jet on a chosen manifold, not a bare tensor.

Geometric kernel & type system.

Beneath the managers is the kernel itself: the category C of manifolds, bundles, and jet types, equipped with its scheduler (composition plus jet propagation) and curvature-aware memory logic. This is where the mathematics from Sections 2 and 3 lives.Backend implementations.

PyTorch, JAX, and similar frameworks sit below as (ideally) interchangeable backend implementations. To really live inside this stack, today’s tensor libraries must be mathematically upgraded: their autodiff engines extended to support k-jet bundles, functorial Jacobian/Hessian operators, and holonomy-aware updates, instead of the current program-bound gradient pipelines built around stackedgrad/jacfwd/jacrevtransforms.Hardware.

Finally, GPUs/TPUs/CPUs are just the physical substrate. The OS shields geometric code from hardware details in the usual way: we can, in principle, change accelerators without rewriting the mathematical layer.

4.3. What this buys you in practice

For AI practitioners, this “new OS” view is not an aesthetic indulgence; it changes what becomes easy:

Higher-order information by construction.

Because state is jet-valued, one semantic pass yields value, gradient, and chosen higher-order terms along encoded directions. Instead of stacking nestedgrad/jacfwd/jacrevtransforms and maintaining multiple shadow graphs (as oddly happens now with PyTorch, JAX, etc.), a k-jet carries all the required order-k information in that single pass.Geometry-aligned representations.

Hyperbolic and toroidal manifolds are not post-hoc interpretations but native spaces in which states live. Hierarchy, periodicity, and phase are expressed in the geometry, rather than being laboriously rediscovered in a flat latent.Structured memory and recurrence.

Toroidal memory with winding-number addressing provides a geometric notion of index and cycle, giving a principled scaffold for long-range, repetitive, or phase-sensitive patterns.Backend independence as a design goal.

Modeling backends as functors from the geometric category to tensors makes it possible, in principle, to swap PyTorch for JAX (or a future system) without changing the abstract OS logic. The mathematics and the implementation are cleanly separated.A principled handle on curvature and path-dependence.

Curvature is no longer an accidental artifact glimpsed through occasional Jacobian probes; it becomes a first-class part of the state and connection. Tools like Gardner-style curvature heatmaps turn into diagnostics of the OS itself, not just of an opaque black box.

In short, the geometric AI operating system takes the hidden structure we already see leaking out of current models—curvature, gauge behavior, path-dependent transport—and promotes it to the level of design. Instead of asking flat tensors plus a first-order engine to simulate curved, higher-order phenomena, we build those phenomena into the substrate and let ordinary programming sit on top.

This article comes at the perfect time. What if geometry fundamentally simplefies complex AI training?