Everyone's Wrong About AI Programming — Except Maybe Anthropic

The lens that makes AI coding bugs impossible, and no one told you.

You Don’t Know How to Code with AI And the method that works is the exact opposite of what you’ve been taught

Vibe coding had its moment.

Around 2023, it felt almost magical. You described a problem in natural language, the AI answered with confident-looking code, and for a brief window it seemed like software development had finally been abstracted away. Business idea in, working system out — the dream of tech managers wanting to get rid of what they regarded as annoying developers. Easy peasy!

Then you got screwed. Wasted.

Not because you’ve been lazy. Not because your prompts aren’t clever enough. But because current AI systems cannot take a real business idea (messy requirements, edge cases, implicit constraints) and produce code that actually works.

What replaced the dream of your CEO is worse: a workflow that defeats itself.

Those upper layers in your tech company didn’t recognize it, but you did immediately, because you work with it daily.

You prompt. The AI generates code that looks fine — deep waters look still — sometimes even elegant. But the CEO isn’t beside you when you run it.

However, a closer look shows you the bad side of AI-generated code: the errors aren’t localized, they aren’t clustered . They’re scattered across the codebase. Innocent-looking lines sit next to logic traps, clean abstractions hide dangerous assumptions, and mixed in with harmless bugs you find code that isn’t just wrong but actively dangerous: security holes, data corruption paths, failure modes you would never have written yourself.

Congrats. You’ve run into what’s called semantic drift — and if you’re not a developer, here’s what the visual nightmare looks like:

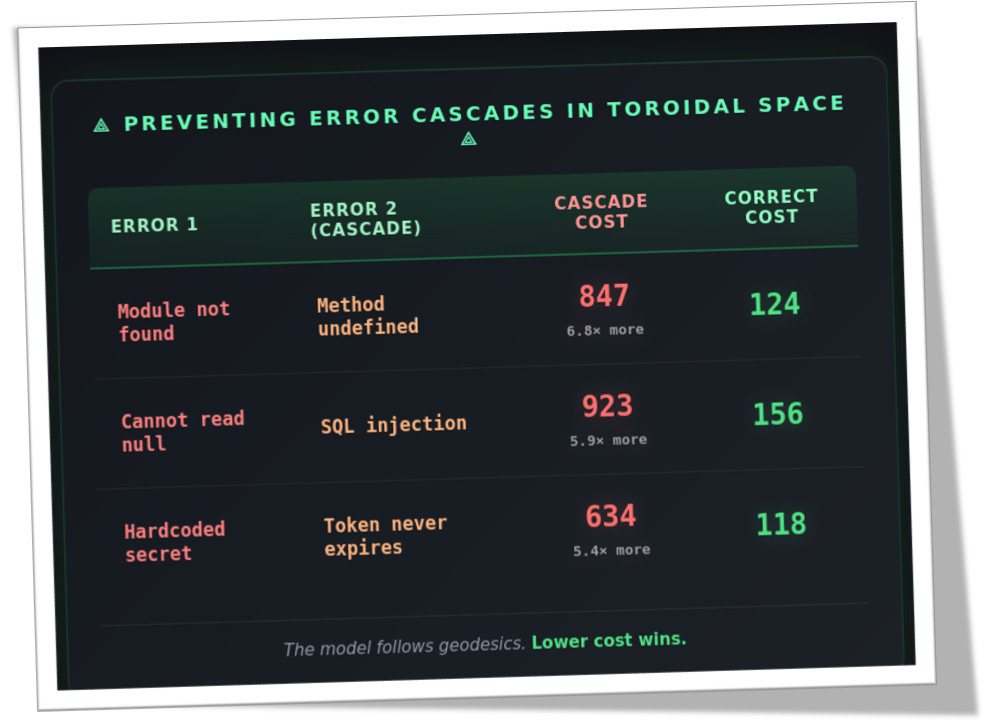

You ask your AI copilot to fix a Module not found error and cool, the code runs now. Except — wait — now it’s Method undefined because the AI just made up an API that doesn’t exist. You ask the copilot to fix that, and suddenly SQL injection pops up because the AI built the query with string concatenation like it’s the early 2000s. You ask it to fix that too, and now you’ve got Token never expires, wow a security hole, wide open!

You close the copilot. You fix it yourself.

Your copilot isn’t stupid. It’s trapped. Current LLMs operate in flat embedding spaces where every direction costs the same( yeah, including the wrong ones). The path from working function to SQL injection nightmare costs exactly as much as the path to correct code: nothing. The model has no geometric reason to prefer one over the other. So it drifts. And you end up chasing after it.

That’s not an AI problem.

That’s a map problem.

The good news? maps can be redrawn.

And that’s exactly what we’re going to do, in a much easier way than the AI industry keeps patching without fixing the problem.

No, we don’t need to rebuild the AI from scratch, or fine-tune it, and much less throw more parameters at it. We’re going to change the terrain it walks on: give it a geometry where drifting toward bugs costs more than drifting toward correct code.

Same model and same infrastructure — but here’s the catch you need to pay attention to: we’ll use a different space where the AI operates and lives.

The Geometry That Actually Works

The solution? A curved toroidal space — the simplest geometry that gives us what we need: periodic structure and a well-defined notion of distance. On top of it, we place a Lyapunov energy landscape. Together, they let an AI copilot see a proper map: one where the path toward correct code is downhill in energy, and the path toward bugs is uphill.

And here's the surprise: Anthropic is taking notes — to the point of publishing research on curved manifolds inside Claude itself.

Note: In January 2026, Anthropic published When Models Manipulate Manifolds, showing that Claude represents information on curved manifolds with geometric transformations. They found the geometry. They’re observing it. What they haven’t done yet is engineer it — deliberately curving the space to make error paths expensive. That’s the lens we’re building here.

Yep, these are the same three error pairs we saw in the flat-space example earlier. The only change is the geometry: once we move to a curved space, the cost structure becomes visible… and the difference is impossible to miss.

Below: the equations, the architecture, and the cost breakdown. For paid subscribers.