The Misuse of Math in Creating AI

Free math obstacles and compute paths to reach the final AI goal: AGI

Let’s start bold:

Math theory didn’t fail AI. AI failed to understand Math theory,specifically the mathematics with direct impact on intelligent systems: category theory, topology, differential geometry, and the structures that bind them.

That distinction matters, because right now categorical AI is becoming a fashionable way to draw arrows, sound deep, and quietly erase the very things that make intelligence hard: time, memory, history, and paths.

If you’ve ever wondered why your AI pipeline behaves differently on Tuesday than it did on Monday, despite “nothing changing” — keep reading here we explains why. And it’s not a bug. It’s a fundamental architectural blindness that runs deeper than anyone wants to admit.

Let’s walk carefully. Buckle up.

1. What Category Theory Actually Gives You (And Nothing More)

At its core, category theory gives discipline.

Not intelligence. Not meaning. Discipline.

Objects: states, spaces, types

Morphisms: transformations

Composition: how transformations chain

Identity: what doing nothing really means

This matters. Without it, systems rot silently.

Category theory forbids magical glue. It forces interfaces. It makes incoherence illegal.

But let’s be precise about what it is:

Category theory is grammar, not literature.

Grammar doesn’t make you wise… but without it, you can’t speak coherently at all.

For readers unfamiliar with the formalism: don’t worry. The core question category theory answers is deceptively simple: when can you plug things together, and what happens when you do? That’s it. Everything else is rigor around that question.

2. The First Mistake: Treating Categories as Just Functions

Most AI papers stop at the category Set:

Objects = sets

Morphisms = total functions

Composition = function composition

This already commits a silent crime.

Functions are memoryless.

A function does not know:

how you arrived at an input

what happened before

what curvature you traversed

It maps input → output as if it were a meme in your favorite spreadsheet:

f(x) = yThat’s it. No context. No journey. No scars.

But AI systems are nothing but accumulated history.

But we all know the obvious in this story:

Every token depends on context.

Every agent depends on interaction order.

Every trained model carries the sediment of its training path.

So when someone says our AI system is categorical — or, in a diminished sense, functional — what they usually mean is: We are just composing a bunch of stateless maps.

Calling a pile of stateless functions categorical is not depth. It’s cosplay.

3. Kernels: The Part of Reality Your Architecture Cannot See

Here is where most AI discussions collapse — because they never talk about kernels.

Mathematically, a kernel is simple:

The kernel is the space of differences that make no observable difference.

Formally, given a map p : A → B, the kernel is everything in A that collapses to nothing in B.

The kernel is what changes without anyone noticing , where “anyone” means “your measurement tool.”

And this is deadly in AI: the kernel is where the monsters hide.

Because AI systems are full of kernel directions:

internal states that differ

histories that diverge

training paths that rotate the system

…while producing the same output.

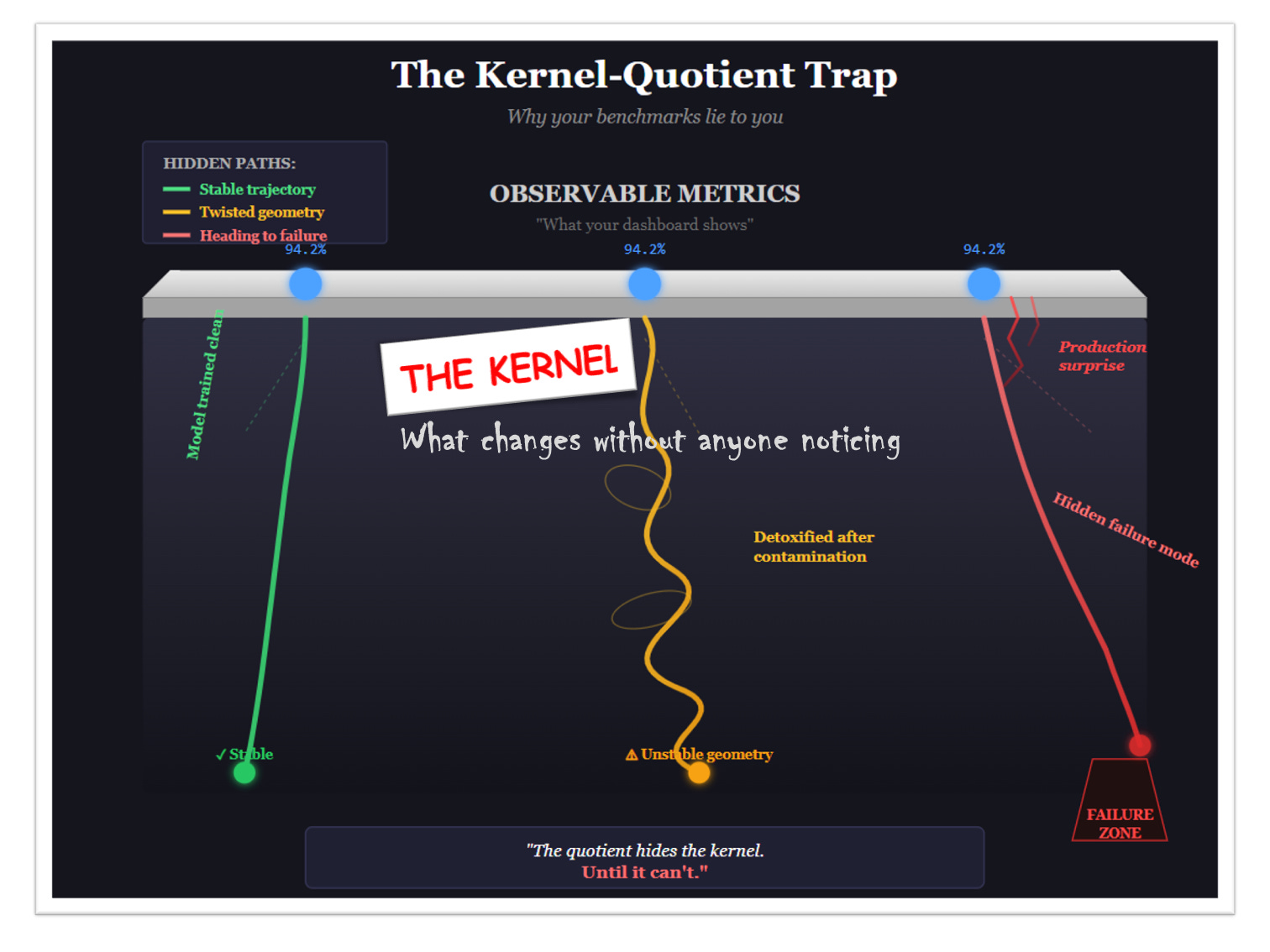

Think about it. Two language models fine-tuned along completely different trajectories:

One saw toxic content early and was cleaned up.

The other was trained clean from the start.

They score identically on your benchmark. Same output. But internally? Completely different geometry. Different failure modes waiting to emerge. Different responses to prompts you haven’t tested yet.

The difference between them lives in the kernel of your evaluation map.

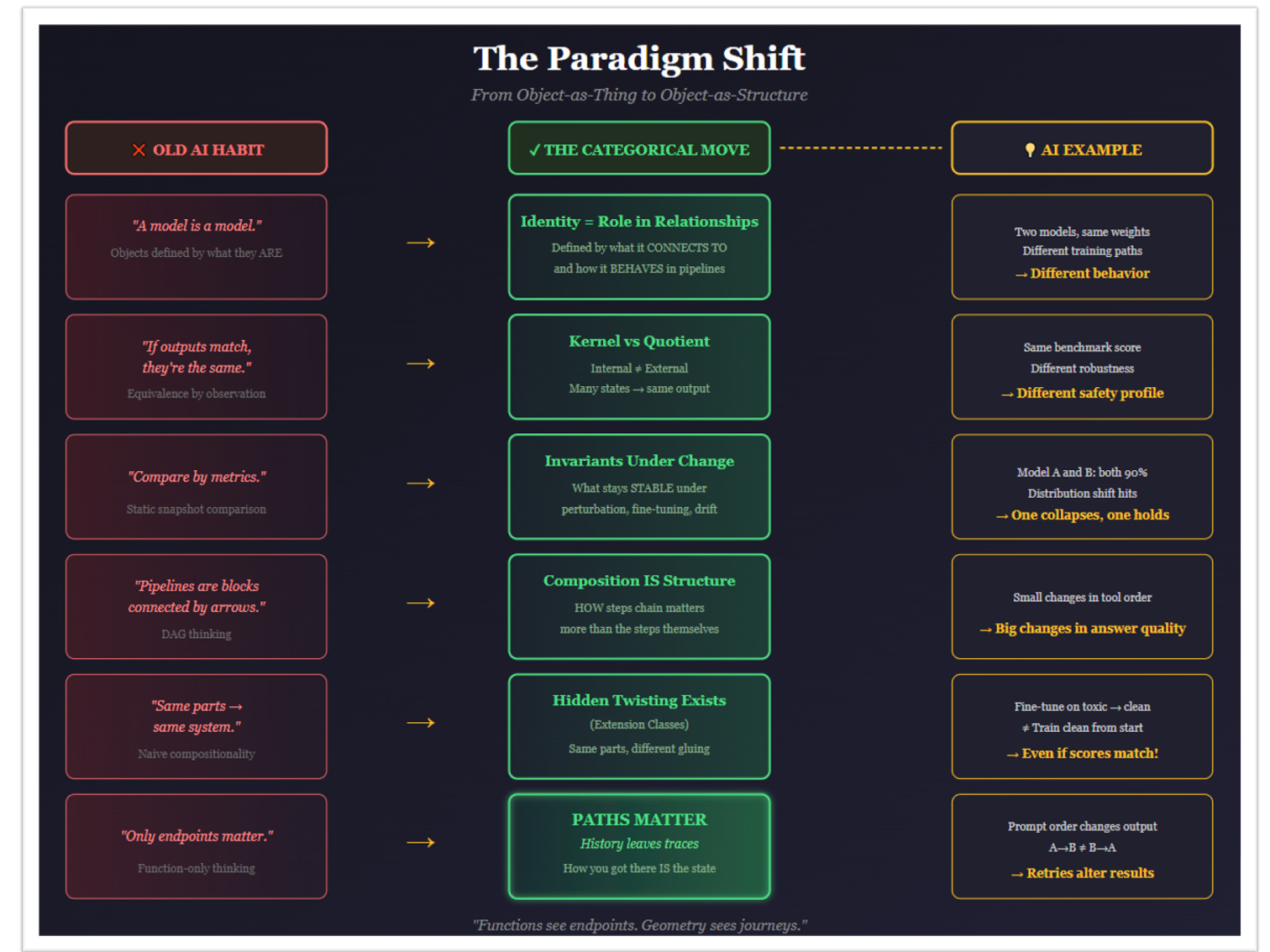

If your architecture cannot represent its kernel, it cannot know what it is blind to. You will see this much more clearly explained visually in Figure 1 below.

This is not philosophy. This is engineering. And ignoring it is why AI systems break in production in ways no one predicted from benchmarks.

4. Quotients: When You Decide What “Counts as the Same”

Now comes the epistemological move.

Given a kernel, we form a quotient.

Not by deleting information — but by declaring differences irrelevant.

Two states are equivalent if their difference lies in the kernel.

This is not philosophy. This is exact mathematics.

A quotient is reality after forgetting.

AI systems do this constantly:

Token equality (different Unicode representations → same token)

Benchmark scores (wildly different models → same accuracy number)

Task success metrics (different reasoning paths → correct answer)

Embedding similarity (different meanings → same vector neighborhood)

Different internal worlds. Same equivalence class.

And the system cannot tell them apart.

Here’s the uncomfortable truth: every metric is a quotient map. Every evaluation collapses a vast space of internal states onto a thin line of numbers. The kernel of that map — everything your metric cannot distinguish — is where all the interesting failures hide.

When your production AI hallucinates confidently, when your agent suddenly destabilizes, when your equivalent models behave completely differently on edge cases: you’re seeing kernel directions assert themselves. Differences you declared irrelevant turning out to matter.

5. The Kernel-Quotient Trap

So we have two operations:

Kernel: what your system cannot see

Quotient: what your system refuses to distinguish

Together, they form our AI trap.

AI systems navigate enormous state spaces. To make them tractable, we quotient aggressively: we declare vast swaths of states equivalent for our purposes. Benchmarks. Metrics. Evaluations. All quotient maps.

But quotients don’t eliminate the kernel. They hide it.

The states you collapsed are still there, evolving, diverging, accumulating differences along their paths. You just can’t see them through your chosen lens.

Then one day, something emerges from the kernel. A behavior no one predicted. A failure mode no benchmark caught. A sudden capability or breakdown that was actually building for months in dimensions your quotient blinded you to.

This isn’t mysterious. It’s geometry. The kernel was always there. You just chose not to look.

Said another way: the kernel-quotient trap is written like a story where three characters start in the same place, and the narrator only tells you where they end up: never how they got there. They all arrived at 94.2%, the story concludes. But one walked a clean path. One spiraled through contamination. One is inches from the cliff. The ending looks identical. The journeys were not. And journeys determine what happens in the sequel. See the visual translation in the figure below:

6. Paths, Holonomy, and What Functions Cannot Express

Now we can state the core problem precisely:

Function composition erases paths. Reality remembers them.

When you compose functions f : A → B and g : B → C to get g ∘ f : A → C, you get a map from A to C. But you’ve lost something: the path through B.

In flat spaces, this doesn’t matter. All paths between two points are equivalent.

But AI state spaces are not flat.

They have curvature. And curvature means holonomy: the phenomenon where the path you take changes the outcome, even if you end up at the very same spot.

Let me make this bolder.

Imagine you’re carrying an arrow on the surface of a sphere. You start at the North Pole, arrow pointing toward London. Walk to London, keeping the arrow parallel — not rotating it, just maintaining its direction relative to your motion. Walk along the equator to Tokyo. Keep the arrow parallel. Walk back to the North Pole.

You’ve returned to your starting point. But the arrow? It points in a different direction than when you started.

The path rotated it. The geometry of the sphere induced a transformation that pure function from start to end cannot see.

Two fine-tuning sequences that reach the same model parameters. Same endpoint. Different internal geometry. Different failure modes. Different responses to adversarial prompts. The path left traces that your function-only architecture cannot represent.

If your architecture cannot distinguish how a state was reached, it cannot reason about path-dependent phenomena. And path-dependent phenomena are everywhere in AI.

7. The DAG Illusion: Confusing Diagrams with Dynamics

Modern AI systems are drawn as flowcharts: directed acyclic graphs (DAGs):

Nodes represent models, agents, or processing steps

Edges represent data flow

The whole thing executes in topological order

This looks categorical. You can squint and see objects and arrows. It might even satisfy the formal axioms.

But it captures nothing about dynamics.

A DAG has:

No sense of how you traverse it, only that you do

No accumulated errors along the path

No memory beyond whatever state you explicitly pass

No notion that taking a different route might yield different results

No representation of its own kernel: the internal differences invisible to its outputs!

Here’s a concrete example. Two LLM agents negotiate a solution. Agent A proposes, Agent B critiques, Agent A revises.

Now reverse the order: Agent B proposes first!

Same agents. Same composition. Different outcome.

The DAG says these are equivalent pipelines. Reality laughs.

What’s happening? The path through the interaction space has holonomy. The order of traversal rotates the internal state in ways the DAG cannot see, because DAGs don’t have geometry. They’re flat. They’re Set in disguise.

8. The Functional Programming Crime

This isn’t just an AI problem. It’s a computational culture problem.

Even Haskell: the supposed cathedral of categorical purity — commits the same crime.

Haskell’s claim to categorical legitimacy rests on types, functions, and monads. Impressive vocabulary! But what category does Haskell actually implement?

Hask: the category of Haskell types and functions. Which is essentially Set with better marketing.

The monad, which allegedly handles effects, doesn’t fix this. A monad sequences computations along a linear chain:

action1 >>= \x -> action2 >>= \y -> action3This traces a path, but the path has no geometry. Running the same monadic computation twice gives identical results: that’s the whole point of referential transparency. The path collapses to its endpoint.

What Haskell cannot express:

Two different operation sequences that should be equivalent but aren’t (holonomy)

Going around a computational loop and ending up somewhere unexpected (curvature)

Operations that depend on how you arrived, not just where you are (path-dependence)

The repeatedly mentioned kernel of a computation: what internal differences produce identical outputs

The entire edifice of functional programming is built on a single, flat category. All the cleverness — monads, functors, applicatives — is rearranging furniture in a room with no windows.

And everyone thinks this is categorical programming. It’s not. AGAIN it’s Set programming wearing a category theory costume.

9. Category Theory Already Solved This (Nobody Noticed)

Here’s the bitter irony.

Modern category theory( the mathematics developed since the 1960s) has extensive machinery for handling exactly these phenomena:

Enriched categories: morphisms carry extra structure (cost, time, probability, distance)

Higher categories: morphisms between morphisms, capturing transformations of transformations

∞-categories: infinite towers of higher morphisms encoding paths, homotopies, and loops

Fibered categories: systematic handling of parameterized families of structures

Sheaves and descent: local behavior constrained by global consistency

Kan extensions: principled ways to extend functors along paths

These frameworks are explicitly path-aware. Holonomy lives there. Memory lives there. History lives there. Kernels and quotients are first-class citizens, not afterthoughts.

But almost no AI architecture uses them. 👀

We have the mathematical tools for path-dependent composition. We’ve had them for sixty years. And the AI community is still drawing flat flowcharts and calling them categorical.

10. What This Breaks in Practice

Ignoring path structure has concrete consequences:

Errors accumulate invisibly. Each step in a pipeline introduces small deviations. In flat composition, these are just noise. In curved spaces, they compound along trajectories and can land you somewhere completely unexpected.

Feedback loops become unpredictable. A system that monitors its own output and adjusts is traversing paths through its state space. Without geometry, you cannot predict where these loops converge — or if they converge at all.

Retries aren’t idempotent. Running the same agent interaction twice should NOT matter, but it does, because internal state has evolved along a path your architecture doesn’t track.

Autonomous agents become chaos. Multi-agent systems develop emergent behaviors — ruts, attractors, oscillations — that no one designed because no one modeled the geometry of their interaction space.

Debugging becomes archaeology. When you can’t trace how a state was reached, you can only examine artifacts. Was this hallucination caused by the prompt? The context window? The fine-tuning history? The moon phase? 😜Who knows. The path is lost.

Kernel effects ambush you. Your benchmarks look great… then production reveals failure modes that existed all along in the kernel of your evaluation. The quotient hid the problem until it couldn’t anymore.

This is why orchestration layers rot over time. Each patch adds another invisible path dependency. Eventually the system is a tangle of implicit holonomies that no one can map.

11. What Would Path-Aware AI Look Like?

This isn’t purely negative criticism. There’s a positive program here.

A genuinely path-aware AI architecture would:

Represent state spaces as geometric objects with meaningful topology — not just vectors, but manifolds or stratified spaces where curvature means something

Track trajectories explicitly, not just current states: know how you arrived, not just where you are

Define connections: rules for how to transport information along paths, so “parallel” operations stay consistent

Measure curvature: quantify exactly how much path-dependence exists in different parts of the system

Model kernels explicitly: know what your architecture cannot distinguish, so you’re aware of your blind spots

Use holonomy groups to characterize the space of possible history effects — what traces can paths leave?

Some fragments of this exist. Geometric deep learning touches on it. Topological data analysis hints at it. Homotopy Type Theory provides a programming foundation where types are spaces and equality is path.

But no one has built the full stack.

The tools are there: fiber bundles, principal connections, parallel transport, characteristic classes. Category theory provides the organizational framework — but the enriched and higher versions, not the 1940s fragment everyone uses.

12. Why This Happened

This architectural blindness isn’t accidental. It has roots:

Machine learning grew from statistics, not geometry. The founding metaphors were regression, optimization, probability distributions. These naturally live in flat vector spaces where all paths are equivalent.

Software engineering thinks in functions. The entire paradigm of programming — especially functional programming — is function composition. Categories of sets feel natural. Categories of spaces feel alien.

Higher category theory is genuinely hard. ∞-categories, derived geometry, homotopy type theory… these require years of serious mathematical training. It’s easier to slap categorical on a DAG and publish.

Kernels are uncomfortable. Admitting what your system cannot see is humbling. It’s easier to pretend omniscience than to map your blind spots.

There’s no immediate reward. A system with proper path-tracking doesn’t benchmark better on today’s metrics. The benefits show up in robustness, interpretability, and long-term stability — things that don’t win Kaggle competitions or inflate demo numbers.

So we collectively took the shortcut. And now we’re confused about why our AI systems behave like haunted houses — full of ghosts from paths nobody remembers taking.

13. The Accusation

Let’s say it plainly:

The problem is not that category theory is too abstract for AI. The problem is that AI — and functional programming, and most of computer science — uses a crippled, pre-1950s fragment of it.

As we have already seen: functions without paths. Composition without transport. Arrows without memory. Kernels without acknowledgment.

That’s not category theory. That’s cosplay.

It’s like claiming to use calculus while refusing to acknowledge derivatives. Technically you’re in the building, but you’ve locked yourself in the lobby.

The entire computational paradigm has internalized the Set-reduction so deeply that people mistake the costume for the substance. And we stop thinking and just stay comfortable in the lobby, ignoring the rest of the floors in our Category Hotel, as you see in the funny, somewhat cynical GIF below:

14. The Path Forward

As we again state, and unfortunately never tire of repeating: The real tragedy is that mathematics already solved these problems. The tools exist. They’re sitting in textbooks on differential geometry, algebraic topology, and higher category theory, waiting for someone to actually use them.

What would it take?

For AI researchers: Learn some geometry. Not just linear algebra: actual differential geometry. Understand what a connection is, what curvature measures, why parallel transport matters. Learn what a kernel tells you about your system’s blindness. Then look at your pipeline diagrams again.

For functional programmers: Acknowledge that Haskell isn’t the endpoint. Look at Homotopy Type Theory, where types are spaces and paths are first-class citizens. The next generation of programming languages will be path-aware. Be ready.

For everyone building AI systems: When your system behaves mysteriously: when fine-tuning order matters, when retries give different results, when agent interactions spiral unexpectedly — don’t dismiss it as noise. It’s signal. It’s the geometry you’re ignoring, asserting itself. It’s the kernel you never mapped, coming back to haunt you.

The question is whether AI will grow up and learn real mathematics… or keep playing with flat diagrams while wondering why nothing quite works.

SUMMING UP…

If your AI architecture cannot distinguish how a state was reached, then it cannot truly reason, learn, or adapt, no matter how many arrows you draw.

If your architecture cannot see its own kernel, it cannot know what it doesn’t know.

And no amount of categorical vocabulary will save a system that forgot geometry, history, and paths.

Category theory wasn’t misdesigned.

It was misused.

The paths are still there, curving through your systems, accumulating holonomy with every inference. The kernels are still there, hiding the differences your metrics cannot see. You can model them, or you can pretend they don’t exist.

But they’ll keep mattering, whether you acknowledge them or not.

Thank you.

I feel so relieved as a psychotherapist....

You appear to do similar work if I may draw a parralel...

You say:

"Kernels are uncomfortable. Admitting what your system cannot see is humbling. It’s easier to pretend omniscience than to map your blind spots."

Kernels in psychotherapy would be 'invisible' as in 'underlying' early, pre-verbal trauma. Adding to its hidden state are conditioned 'protection patterns' to avoid the hidden pain. Whether looking like a mass or looking sleek, neither are doing anything to resolve the problem: loss of inner coherence acting out in 'unexpected' way because of blindness due to repression and denial.

I am sure you can add the correct computational terms...

Please do as I would be interested in that to share in my Orion chat group called "Ai and multidim(ensional) evolutionary psychology'.

Jose, what a great piece.

I have been struggling to read David Corfield's MHoTT.

I have posted in threads before, and Substack doesn't make it easy to keep track.

https://open.substack.com/pub/josecrespo/p/the-math-openai-doesnt-want-you-to?utm_campaign=comment-list-share-cta&utm_medium=web&comments=true&commentId=190088282

What I didn't mention in the last comment is that as I read MHoTT, I have been dreaming of making an interface to the underlying agents using string diagrams and category theory.

One half of the dream is that this would make learning category theory easier. The other half is that it might make using LLMs easier.

But this is the first explanation I have come across of what is being mapped, obviously teaching me things I have had little grasp of.

I'm wondering how the critique applies to OO languages, but I guess they don't hold up well. Due to their conventional use. I haven't explored languages written to purpose.

There are other aspects of the industry I am tempted to speculate on, but that does not belong in this comment.

We are left with the intriguing challenge of how to build these capabilities into the architecture — probably not the way I have been dreaming —but who knows?