The Winding Numbers: Topology’s Answer to the Birthday Paradox in Current AI

How to Avoid Hallucinations by Preventing Collisions

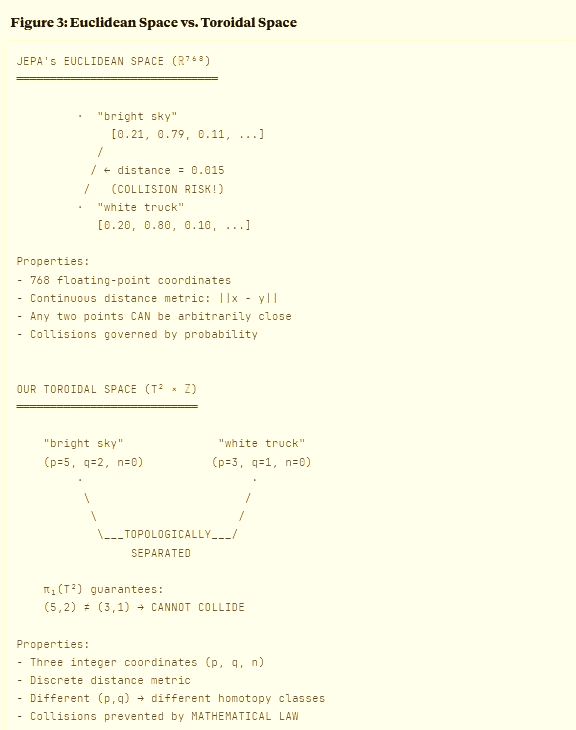

Remember that birthday collision problem? Where “white truck” and “bright sky” end up as neighbors in the same overcrowded Euclidean apartment complex?

Our toroidal model makes collisions mathematically impossible. Not improbable. Impossible.

Here’s how.

What’s a Torus, Really?

A torus is the familiar donut shape — but mathematically, it’s far more interesting than it looks.

Formal definition:

Translation: A torus is the product of two circles. One circle wraps around to form the “tube,” another wraps around to form the “ring.”

Why it’s a manifold:

Locally Euclidean: Zoom in on any tiny patch of the torus surface, and it looks flat — like a piece of regular 2D plane. This is the fundamental manifold property: locally flat, globally curved.

Globally Curved: But zoom out, and the surface wraps around and connects to itself. No edges. No singular points. No crossings. Just smooth, continuous curvature.

Smooth Coordinate Charts: You can cover the entire torus with overlapping coordinate systems (called an “atlas”) that fit together smoothly. This makes it a smooth 2-dimensional manifold.

The Key Topological Property:

Unlike a sphere (which has no holes, genus = 0), the torus has one hole (genus = 1).

This single hole changes everything:

On a sphere, every loop can shrink to a point

On a torus, loops that go around or through the hole cannot shrink to a point

These non-shrinkable loops belong to different homotopy classes

This is the structure that protects us from collisions.

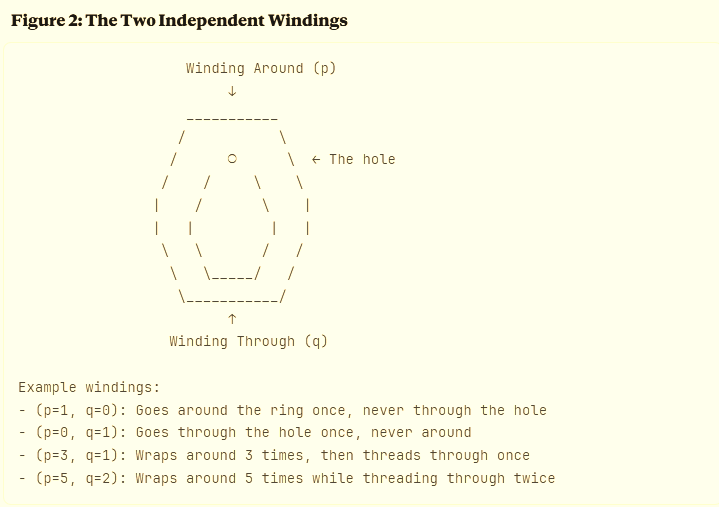

Two Ways to Wind

Imagine wrapping a string around the torus. You have two fundamentally different ways to loop that string:

Around the hole (the “meridian” — like a bracelet sliding around your wrist)

Through the hole (the “longitude” — like threading a needle)

You can combine these moves: wrap around the hole 3 times, then through it once, then around twice more. Every unique path creates a different pattern — a different winding.

In mathematics, we describe each winding with two integers: (p, q)

p = how many times you wrap around the hole (meridian)

q = how many times you go through the hole (longitude)

These are your winding numbers.

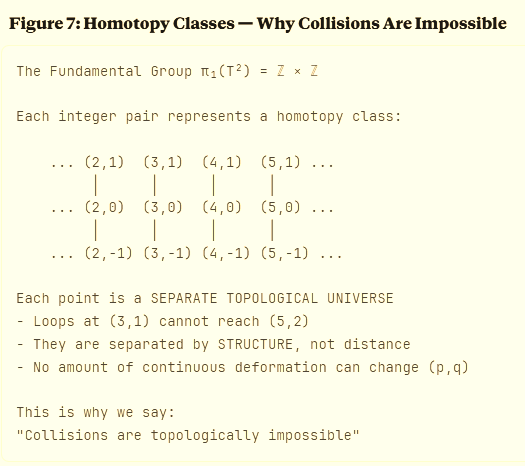

The Topological Guarantee: Fundamental Group

Here’s where it gets beautiful and brutal.

The fundamental group of the torus is:

What this means in plain English:

Every distinct loop on a torus can be classified by two integers (p, q). These integers count how many times the loop winds in each independent direction.

The iron law of topology:

Two loops with different winding numbers (p₁, q₁) ≠ (p₂, q₂) can NEVER be continuously deformed into each other.

Not “it’s hard.” Not “it’s unlikely.” Never. You would have to cut the loop or tear the surface.

They belong to different homotopy classes — different topological universes. A loop that winds (3, 1) and a loop that winds (5, 2) are as fundamentally different as a circle and a figure-8.

This is why collisions are impossible in our model.

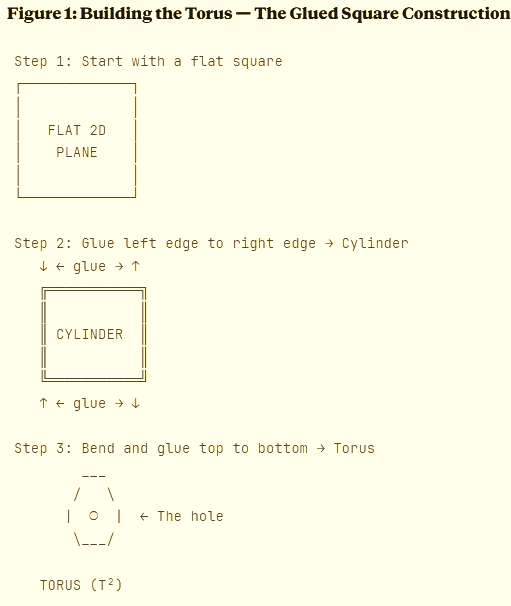

Building the Torus: The Square with Glued Edges

Here’s the most intuitive way to understand the torus as a manifold:

Start with a flat square

Glue the left edge to the right edge → you get a cylinder

Now bend the cylinder and glue the top circle to the bottom circle → you get a torus

What this reveals: The torus is locally flat (it started as a flat square) but globally curved (after gluing). Every point on the torus has a neighborhood that looks like a piece of flat 2D plane, but the overall structure loops back on itself.

This is manifold geometry at its essence: local flatness, global structure.

From Donuts to Concepts

Now map this mathematical structure to AI:

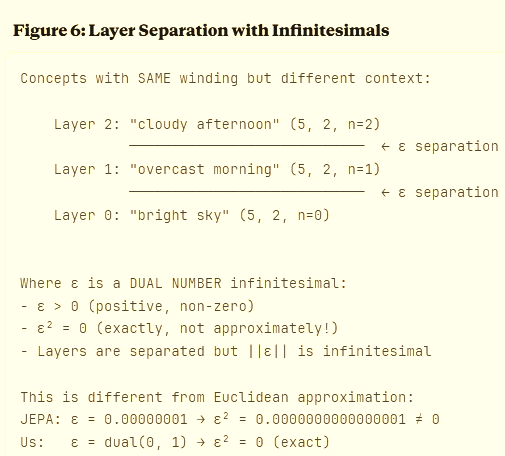

“White truck” gets winding numbers (p=3, q=1, n=0)

“Bright sky” gets winding numbers (p=5, q=2, n=0)

“Cloudy weather” gets winding numbers (p=5, q=2, n=1)

The protection mechanism:

Different (p, q): “white truck” (3,1) vs. “bright sky” (5,2) → topologically distinct homotopy classes → cannot collide by mathematical law

Same (p, q), different n: “bright sky” (5,2,0) vs. “cloudy weather” (5,2,1) → separated by infinitesimal layer distance → ε such that ε² = 0

That third number — the layer index n — handles concepts that share the same winding pattern but need separation. They live in parallel layers, separated by an infinitesimal distance so small that when you square it (ε²), you get exactly zero in our dual number arithmetic.

This three-level structure gives us:

Topological protection (different windings can’t merge)

Infinitesimal layering (same winding, different context)

Discrete addressing (all coordinates are integers or infinitesimals)

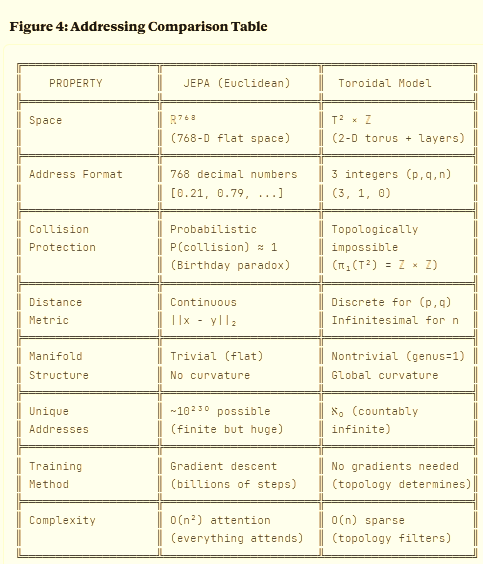

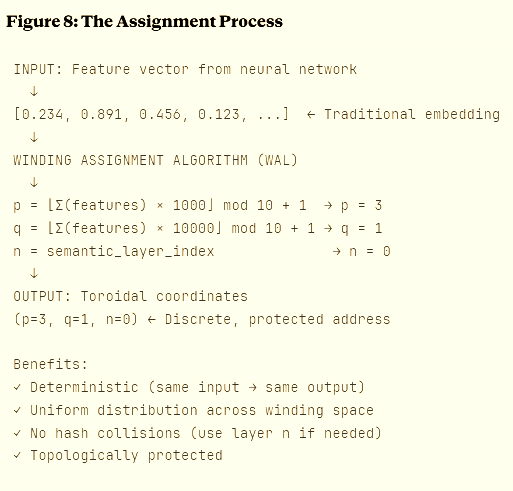

Why JEPA and New AI Architectures Still Fail

JEPA operates in ℝ⁷⁶⁸ — a 768-dimensional Euclidean space where:

Every point is defined by 768 floating-point decimal numbers

Any two points can be arbitrarily close: ∀x,y ∈ ℝ⁷⁶⁸, ∃ε>0: ||x-y|| < ε

Similarity is measured by Euclidean distance: ||x - y||₂

No topological structure — just coordinates floating in space

The manifold structure: trivial — it’s just flat ℝ⁷⁶⁸

The protection mechanism: probability — hope things don’t collide

The collision guarantee: none — birthday paradox ensures eventual failure

Our toroidal model operates in T² × ℤ where:

Every concept is (p, q, n) — three integers/infinitesimals

Different (p, q): topologically protected by π₁(T²) = ℤ × ℤ

Same (p, q), different n: infinitesimally separated where ε² = 0

Distance metric: discrete for (p,q), infinitesimal for n

The manifold structure: rich — locally flat, globally toroidal

The protection mechanism: topology — fundamental group structure

The collision guarantee: mathematical law — different homotopy classes cannot merge

The Math Is Old. The Application Is New.

Topology has understood winding numbers since the 1800s:

Henri Poincaré (1895): Introduced the fundamental group π₁

L.E.J. Brouwer (1912): Developed the theory of covering spaces

Emmy Noether (1920s): Connected topology to algebra

The fundamental group of the torus π₁(T²) = ℤ × ℤ was proven before the first computer was built. Every topology graduate student learns this in their first semester.

We’re not inventing new mathematics.

We’re applying forgotten mathematics to a problem that desperately needs it.

The theory was complete by 1950. But in the rush to scale neural networks from 100 parameters to 100 billion, we forgot that the space you work in determines what’s possible.

JEPA chose the easiest space: flat, familiar ℝᵈ.

We chose the right space: T² × ℤ with discrete addressing and topological protection.

The difference isn’t incremental. It’s categorical — in the precise mathematical sense.

Physical Intuition: Where Toroidal Spaces Appear

This isn’t just abstract math. Toroidal manifolds appear throughout physics and nature:

Phase Spaces: Two coupled pendulums have a phase space that’s a torus — one angle for each pendulum’s position. The system naturally lives on T².

Periodic Data: Time-of-day (0-24 hours) × day-of-year (0-365 days) creates a toroidal data space. The hours wrap around, the days wrap around — naturally forming T².

Complex Analysis: The torus appears as ℂ/(ℤ + τℤ) — the complex plane modulo a lattice. This is the foundation of elliptic functions and modular forms.

Quantum Mechanics: The state space of a particle on a ring is S¹. Two particles on two rings? T² = S¹ × S¹.

Nature already uses toroidal geometry. We’re just recognizing it.

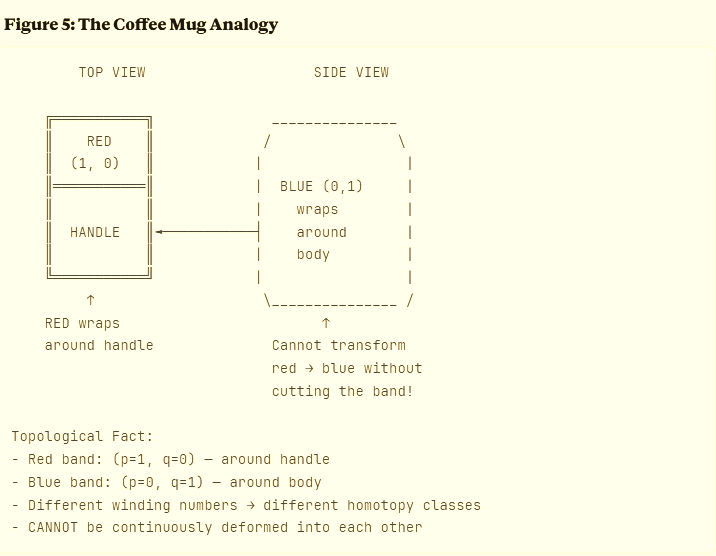

Visualization: The Impossible Collision

Imagine two rubber bands on a coffee mug:

Red band wraps around the handle once: winding (1, 0)

Blue band wraps around the mug’s body once (not touching the handle): winding (0, 1)

You cannot slide the red band to become the blue band without cutting it or breaking the mug.

That’s the topological protection of different winding numbers.

Now imagine your AI:

“Self-driving car” winds through autonomous vehicle concept space: (3, 1, 0)

“Autonomous drone” winds through aerial robotics space: (1, 3, 0)

In JEPA’s Euclidean ℝ⁷⁶⁸: If their 768 coordinates happen to be similar → collision possible

In our toroidal T² × ℤ: Different winding numbers (3,1) ≠ (1,3) → collision impossible by π₁(T²)

One system is protected by probability.

The other is protected by the fundamental laws of topology.

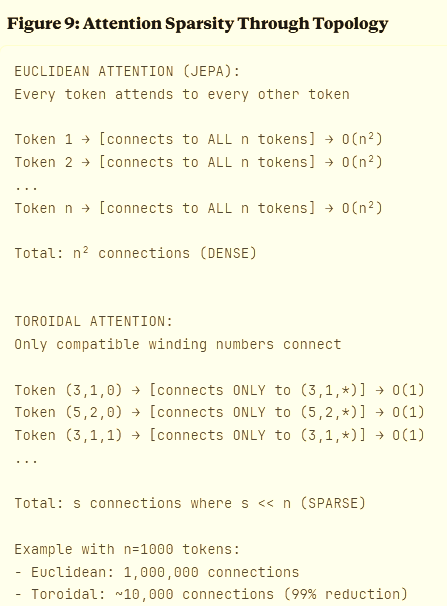

From Theory to Implementation: The Winding Assignment Algorithm

Interactive Thought Experiment

Try this mental exercise:

Imagine a rubber band on your wrist (winding around your arm)

Now imagine a rubber band through a ring you’re wearing (winding through the ring hole)

Try to transform the wrist band into the ring band without cutting

You can’t. That’s topology.

Now replace “rubber bands” with “AI concepts” and “your arm” with “the manifold of meaning.”

That’s our collision protection.

SUMMING UP

Winding numbers aren’t a clever trick. They’re a mathematical inevitability when you choose a manifold with nontrivial topology.

The torus has genus 1 (one hole).

That hole creates π₁(T²) = ℤ × ℤ.

Those integers become your collision-proof addresses.

JEPA sees a flat world where everything can blur together.

We see a curved manifold where identity is preserved by topological structure.

They’re approximating on a sandbox.

We’re building on the bedrock of 19th-century mathematics.