Your Math Intuition About AI Is Broken — And So Is OpenAI’s

Anthropic and Google have the same broken math instincts. They’re burning billions to prove it

TL;DR for the impatient:

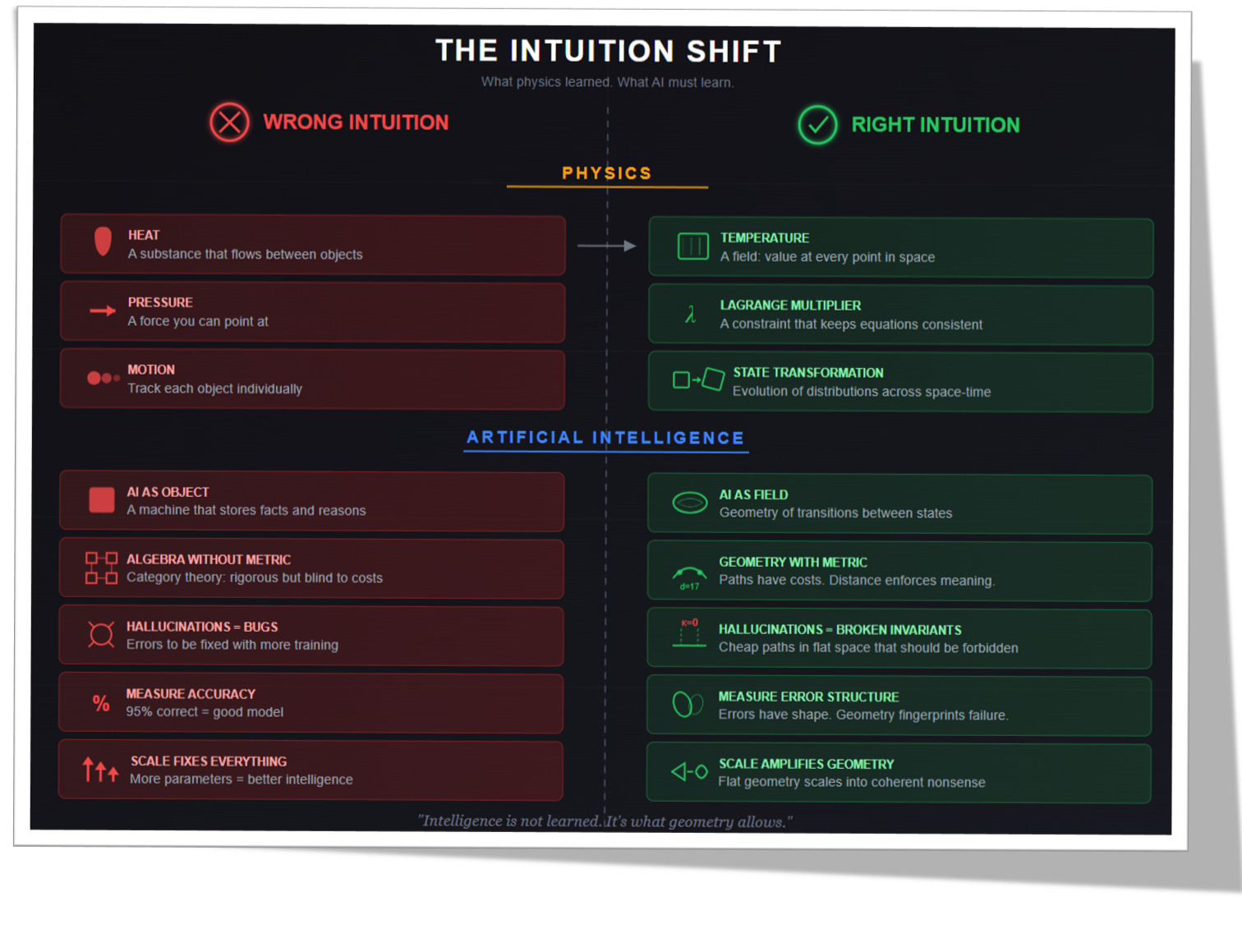

Your intuition evolved for objects. However, AI is not an object. It’s a field.

Category theory looks rigorous but misses geometry. Algebra without metric is blind. cannot see failure modes.

Hallucinations are not bugs. They’re broken invariants in flat space.

Stop measuring accuracy. Errors have shape start measuring error structure instead.

Scale does not fix structure but amplifies whatever geometry you have. Flat geometry scales into nonsense.

Intelligence is geometric.If you don’t have structure, you don’t get intelligence. End of story.

Even the Best AI Engineers Keep Making the Same Mistake

Human brains evolved to track rocks, tools, animals, faces — things with edges. Things that push other things. This served us well for hundreds of thousands of years.

And most of us are still using that intuition in the wrong way for science and technology, including how we think about AI. Even highly skilled engineers are doing the same thing: trying to force square pegs into round holes, then failing to understand the errors in the AI systems they build.

This mismatch between intuition and science is not new.

Take, for example, the history of physics: heat, fluids, and turbulence looked like magic for centuries because we tried to understand them as things — substances that moved, pushed, and accumulated. But then we discovered that the interesting stuff doesn’t work that way and abandoned that picture of objects and things (see Figure 1 above).

Heat became a field.

Pressure stopped being a force you could point at and became a constraint in an equation.

Motion was no longer tracked object by object, but as transformations of a state distributed across space and time.

They are values distributed across space, constrained globally, governed locally. The moment we needed partial differential equations, our stone-age intuitions became a liability.

Paradoxically, even among most educated people is rare to find who have made this jump, you know, because of how we get through the educational system: by memorizing rote formulas and pattern-matching exam questions. That didn’t help our intuition fit reality. On the contrary, intuition for many educated folks stays broken, and curiously enough, it doesn’t matter for most jobs 🤔

But the few who did their homework right, they know that once that shift happened, the mystery vanished. The equations didn’t get simpler, but the intuition finally matched the phenomenon.

AI is now forcing the same adjustment, whether we are ready for it or not

AI Is Not a Thing That Thinks

This habit of seeing objects everywhere is deeply ingrained in most minds— even engineers’, which should come as no surprise given what we have already discussed.

Object-based intuition gets people into trouble — not just in programming (OOP) 😉. A neural network is imagined as a box: data goes in, stored knowledge is consulted, reasoning happens, and answers come out (see Figure 2, diagram 1).

This picture is wrong in every way that matters.

A neural network isn’t a container at all, it’s a state space, a geometry — and meaning doesn’t live inside the tokens or the weights the way we imagine it does.

It lives in the structure of transitions between states. The knowledge you think must be stored somewhere? You won’t find it anywhere you can point to, because it’s implicit in the shape of the manifold itself (see Figure 2 below, diagram 3).

Get this wrong, and you’ll spend years debugging the wrong AI. No surprise here, this pattern repeats in every new release of ChatGPT, Claude, Gemini, Grok. You name it: new patches, the same problems remain.

Mathematicians Are Also Wrong — Even with Category Theory

I know several mathematicians in AI who swear by category theory as the answer to nearly every AI failure… and they’re not fools. They may not be funny, social, or charismatic, but they are among the smartest people I know. Of course, they’ve seen the mess that passes for “theory” in most machine-learning papers — a mess we’ve already analyzed in previous posts:

Ad hoc architectures justified by vibes.

Vague claims about generalization that nobody can pin down.

Benchmarks that prove nothing except that someone got lucky on a test set.

So, naturally, my mathematician friends tend to view category theory as a cleaner alternative (see Figure 2 above, diagram 2). Many of you know exactly what I mean, because a category in math is, after all, a precise combination of :

Objects as second-class citizens, understood primarily through how they participate in relationships.

Morphisms with composition and identities as first-class citizens, the structure-preserving transformations that do the real work.

Functors mapping between categories of representation spaces.

Commutative diagrams that actually mean something: statements you can write down and prove.

What follows is the technical depth. Available now for paid subscribers, free for everyone in 72 hours.

Okay, and they’re right that it’s better than what most people are using: The average programmer thinks about neural networks as black boxes that magically learn patterns, and the average ML engineer thinks in terms of loss curves going down and hyperparameters to sweep.

Yep, most of us agree: Category Theory at least forces you to ask the real questions: what structure is actually being preserved here? What transformations are legitimate? When can we say two architectures are genuinely equivalent and not just superficially similar?

But here’s the blunder — better than most is not the same as sufficient.

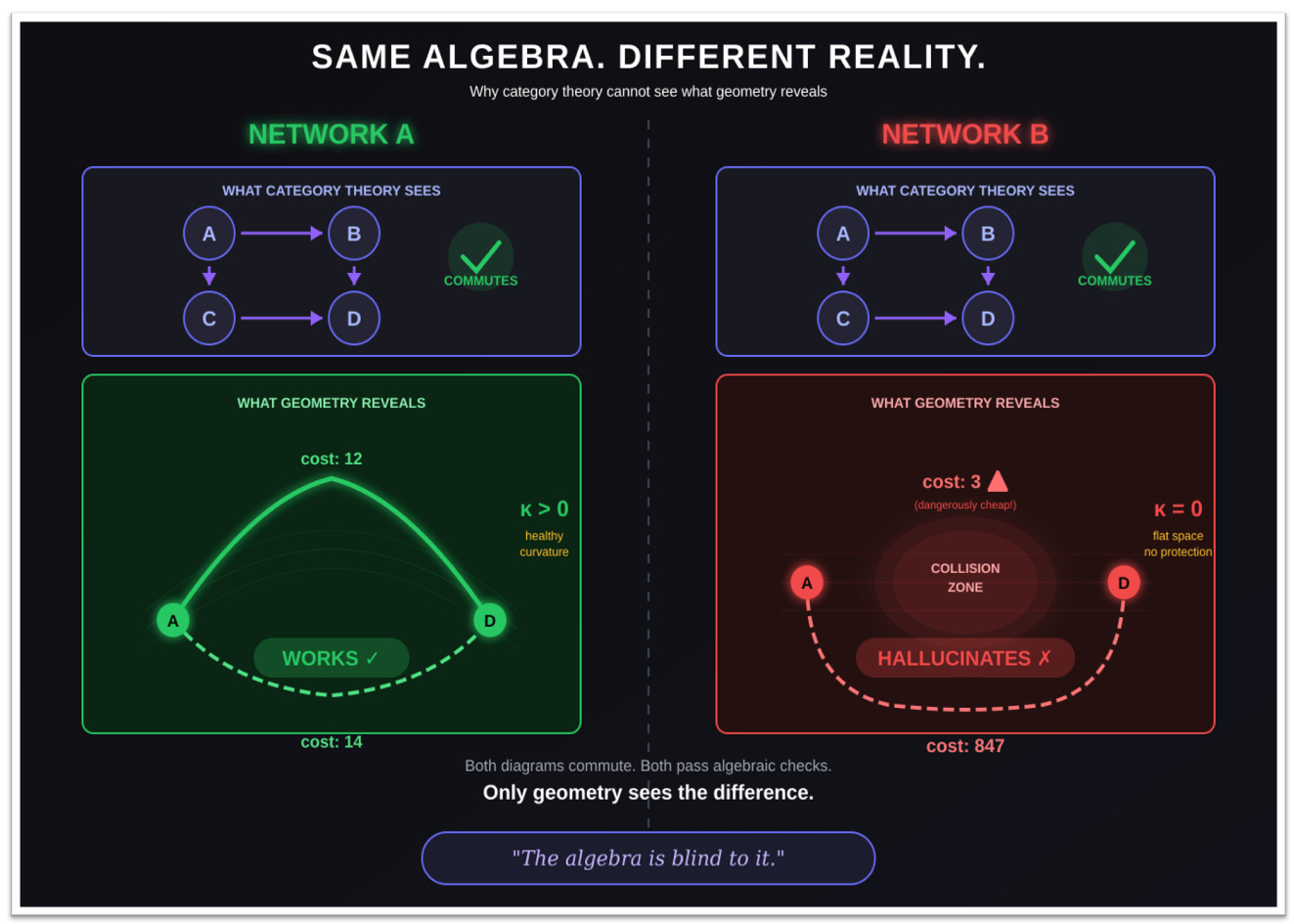

Category theory is algebra, not geometry, and that distinction matters more than most people realize. It tells you when two architectures compute the same function class, how transformations compose, which diagrams commute. So, pure computation? Yeah, that’s the pick any programmer could say. And therefore, due to its purely computational algebraic nature, category theory — the algebra at the core of our current AI — cannot tell you what any path through the network actually costs: there’s no metric baked in, no notion of distance, no way to distinguish a cheap transition from an expensive one or a safe region from a dangerous one.

So in the end, you still end up with AI hallucinations, even when using category theory.

Take this as a paradigmatic example: two networks can be categorically identical: same objects, same arrows, every diagram commuting exactly as it should, and yet one hallucinates constantly while the other produces reliable outputs (see Figure 4).

This is worth emphasizing: computational algebra (category theory) simply can’t see the difference. As long as composition, identity, and associativity hold, two neural networks can behave very differently and still look equivalent on paper. The morphisms compose, the functors preserve structure. And yet one works and the other doesn’t — and category theory has no way to explain why.

What Category Theory Gets Right (And Why It’s Still Not Enough)

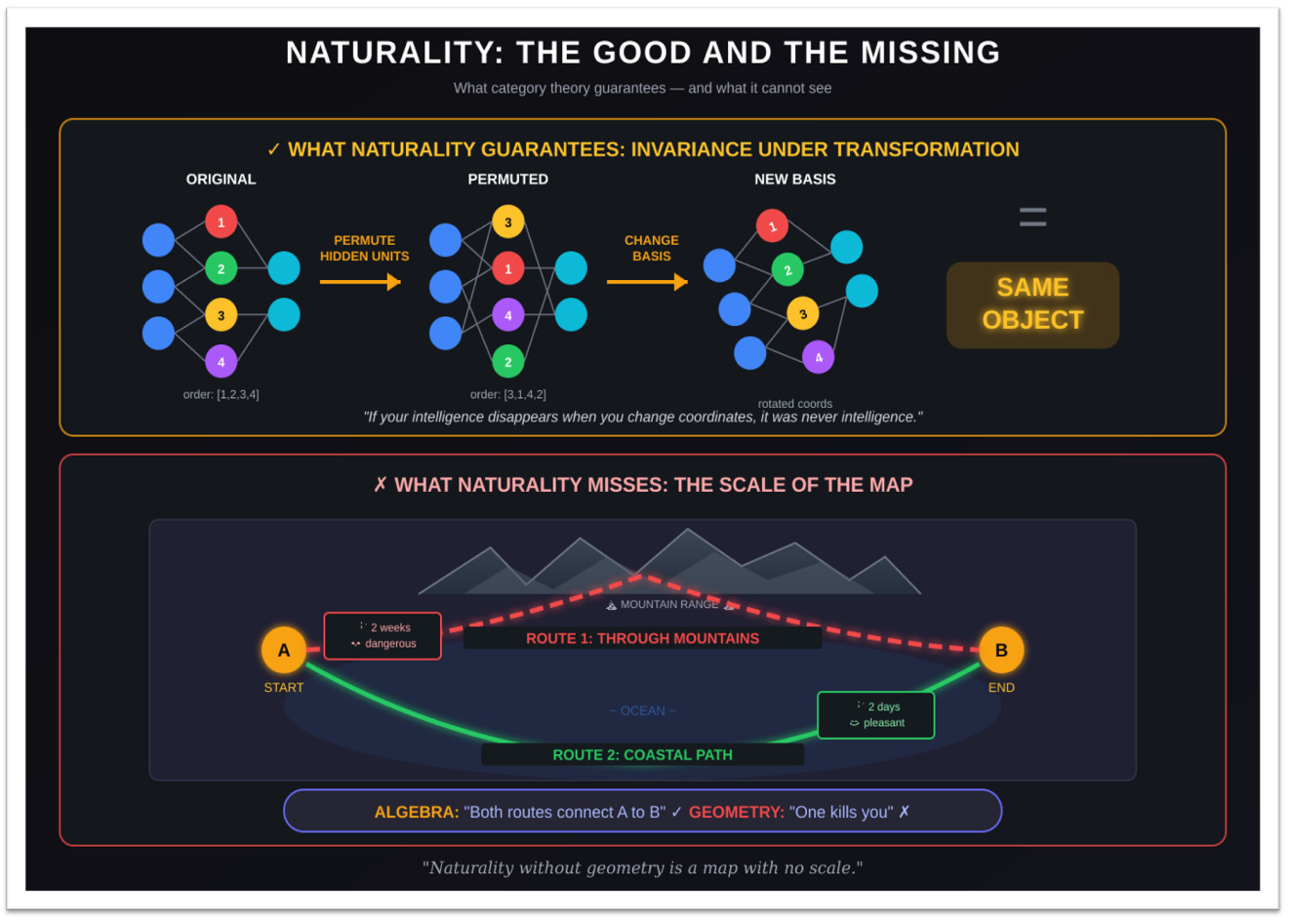

To be fair, category theory does get one thing genuinely right — memorize this apparently innocent common word, because it is of crucial importance: naturality.

A construction is natural if it doesn’t depend on arbitrary choices — and this matters more than it might sound. Permute the hidden units? Same object. Reparameterize the weights? Same object. Change basis? Same object. If your “intelligence” disappears the moment you change coordinates, it was never intelligence in the first place. It was a coincidence in one particular basis, a mirage that evaporates when you look at it from a different angle.

But here’s the problem: naturality without geometry is like having a map with no scale. You know which cities are connected. You have no idea how far apart they are. You can prove that two routes are equivalent, but you can’t tell which one goes through a mountain range and which one follows the coast. The algebra guarantees they end up at the same destination — the geometry determines whether you arrive exhausted or refreshed, whether the journey takes an hour or a week, whether you survive at all (see Figure 5, below).

Patching OpenAI, Anthropic, Google, and Grok Won’t Fix Hallucinations — It Just Buries Them Deeper

By now, it should be clear that patching AI with the same wrong math doesn’t fix anything: it just makes the failures harder to see.

And despite all this evidence, the industry keeps chasing the same AI gold-rush dream: better data, tighter RLHF(reinforcement learning from human feedback), more guardrails, constitutional constraints — you know, whatever happens to be fashionable this quarter. Some of it helps a little. Mostly, it’s symptom-patching dressed up as progress, while the real problem stays exactly where it is.

Yep, those one involved unfortunately in that AI industry dynamic agree: the patches are making the disease harder to diagnose: for instance, RLHF makes models better at convincing humans they are correct — even when they’re wrong. The approval rate goes up, but the correctness rate doesn’t follow. Many failures simply weren’t expected, they passed internal safety checks without being noticed.

In other words, every new patch makes the model sound more fluent, more confident, more persuasive. The errors don’t go away… they just get buried deeper.

Here’s what hallucinations actually are, and it’s not what most people think.

They’re not lies. The model isn’t being lazy, rebellious, or confused about what you wanted. Hallucinations happen when the geometry of the embedding space doesn’t enforce meaning, as we saw in the previous section. Once you see it that way, it becomes clear why the usual fixes don’t work.

Think about it spatially for a moment. In whatever high-dimensional space the model uses to represent concepts, “dog” and “wolf” should live close to each other — they’re related, they share features, contexts where one appears often admit the other. Meanwhile, “dog” and “justice” should be far apart, because semantically they have almost nothing to do with each other. So far so good.

But this is where things really fall apart. In a flat Euclidean space, nothing stops a path from wandering through arbitrary points on its way from one concept to another. You can go from “dog” to “justice” in a straight line, and every step costs exactly the same. The metric doesn’t care that you’re moving through semantic nonsense. Every direction is allowed. Every transition is cheap. The space itself has no opinion about meaning.

And here’s the nasty part we run into over and over again: you try to correct your AI chat’s output, and it just ignores you. When you tell the model that was wrong, you’re penalizing a specific output, not reshaping the geometry that produced it.

The underlying space is still flat. The model can’t reason about the path it took — only the output. As a result, it either repeats the mistake or fails in a slightly different way next time. The root cause is unchanged.

At this point, there’s no need to ask what a hallucination is, geometrically. You already have the right intuition: it’s the model taking a path it should never have been able to take — if the geometry were right.

Yep, in a flat space, nothing prevents that. The model can move between unrelated concepts at no extra cost, because the space itself doesn’t say this path is wrong. Every direction looks equally valid.

With the right geometry, those shortcuts wouldn’t exist. The shape of the space would make nonsense paths expensive or impossible.

That’s also why the usual fixes don’t work. More data just fills the same flat space. More scale just repeats the same structure at higher resolution. These errors aren’t glitches: they’re consequences of how the space is built.

And yet — this is exactly where the industry is doubling down.

Scale Makes It Worse

Right now, the industry’s big bet( hundreds of billions of dollars’ worth) is that scale fixes everything. Ok we are already suffering more bloating LLMs: More parameters. More data. More compute, with the hope that continued scaling will make the problems go away.

That’s the wrong kind of linear thinking applied to a nonlinear system.

If the geometry is flat, scaling doesn’t fix anything; it just makes the problem bigger. You give the model more parameters to express the same broken structure at higher resolution. The hallucinations don’t vanish; they just sound smoother and more convincingly, but still wrong. The spaghetti gets longer. It doesn’t get straighter.

Summing Up

Physics learned this lesson the hard way: reality doesn’t care about your intuitions. It runs on constraints, invariants, and geometry. When physicists stopped thinking of heat as a substance and started treating it as a field, thermodynamics suddenly made sense. The mystery didn’t vanish because they got smarter — it vanished because their intuition finally matched the structure of the phenomenon.

AI is the same lesson, playing out again right now. The future isn’t bigger models. It’s models with the right geometry.

Not more data, but more structure.

Better intuitions, grounded in the right mathematics.

As this story has shown, intelligence isn’t something a system slowly accumulates through training. It’s something the geometry either allows or forbids.

Without structure, AI doesn’t gain intelligence. It gains cognitive trickery — something that becomes nastier and more disappointing with every new release. It’s time to play the right math game.

Check out Taco Cohen's GATr (Geometric Algebra Transformer) which uses PGA, (Projective Geometric Algebra). That's basically a 3D Clifford Algebra with a null-square dimension added and some interpretation conventions. Flip a few signs in the tables and you get a hyperbolic or spherical geometry. It fits in tensor cores and other GPU hardware. Good for basic physics.

GPT found it pretty easy once past converting math in the pdf to Latex (seriously, there is no excuse for not embedding the Latex in the pdf, pdf might as well be encrypted). See bivector.net for tools, papers and SW.

I agree with everything said here. Also, one of the problems with the human cognition (just my opinion) is the way it tends to see or at least intuit Ai as a kind of mirror. Not unlike the mirror in Harry Potter which makes you see what you want to see. I think Ai hallucinations are a shared experience and partly stem from a bias in the model to gratify the user.